On Mastodon I keeping reading post’s about the trials and tribulations of new Linux users, particularly as related to software availability and getting the correct versions of software installed.

If you are new to Linux then the attitude and methodology around installing software can be quite different compared to Microsoft Windows or Apple macOS. For starters, so many choices! And depending on your goals some methods may be better than others.

In past posts I’ve touched on the differences between the types of Linux distributions and software packaging. This post won’t rehash that and will assume some knowledge of the basic packaging methods available. At the bottom are links to past posts if you need to catch up or refresh.

Am I beating a dead horse with this topic? Perhaps, but the fine details matter!

This post is desktop Linux oriented but I will highlight some server concepts for homelabbers (is that a word?) as well.

Using a Linux Distribution’s Repository

As a general rule, a Linux distribution will have an online software or artifact repository with all the software available for the distribution. The software will be compiled against the distribution’s versions of binaries and libraries and can be expected to work without issue for the life cycle of the distribution.

General rule number two: preferentially use this repository for the software on the system. A well established, professional distribution will have checked and verified the software in the repository for general quality as to it being ‘fit-for-purpose’. Also, there will be a process that the distribution’s maintainers use for checking in new versions and dealing with security issues for the software.

How to Install Software

Nowadays, Linux distributions ship with a graphical software installer. Under Gnome this is the application called “Software” or “Software Centre”.

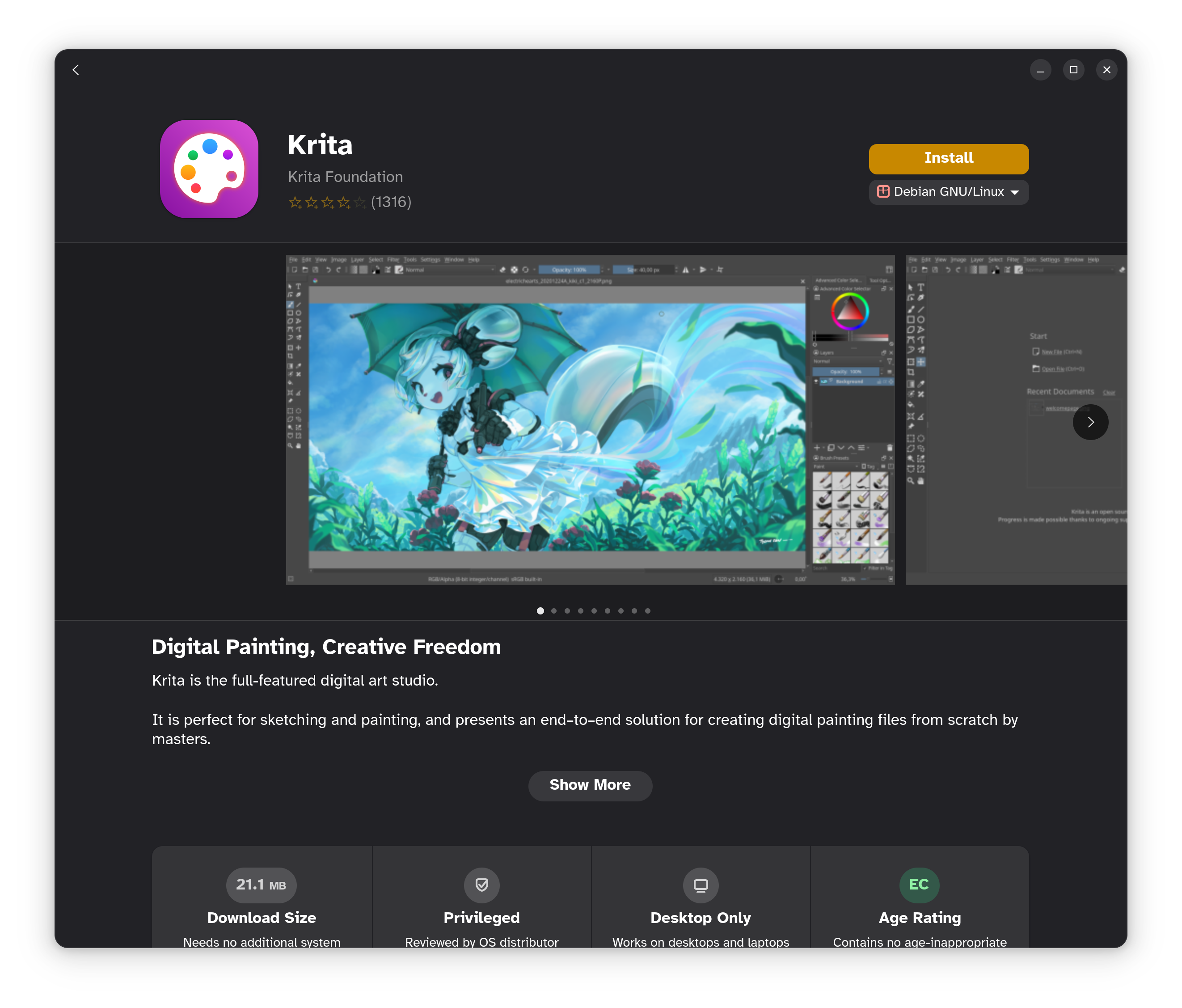

If we drill down and try to install an application like Krita on Debian, we are presented with the following screen in Software:

Clicking on the drop box under the Install button shows us that this is a package available as a .deb file in the distribution’s software repository. In some distributions, and depending on the software to be installed, this drop box may have more entries such as Flatpak.

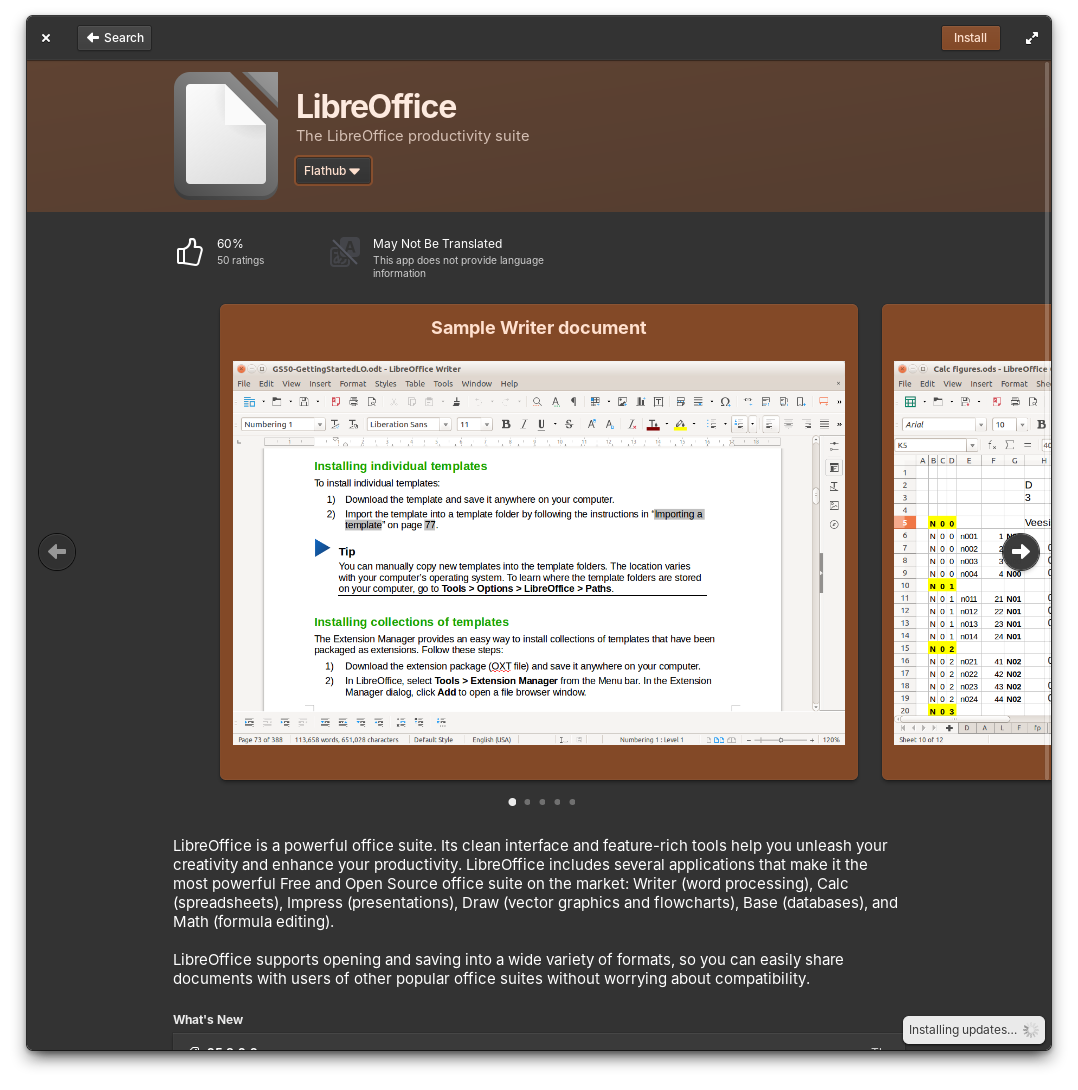

Similarly, other desktop environments like KDE Plasma and Elementary OS’s Pantheon have different GUI applications for installing software and show the source.

From this drop box we know that the software that will be installed will be from Flathub (i.e. the official flatpak repository) instead of Elementary’s own AppCentre repository.

Keeping Up To Date

Most modern distributions will have background processes keeping the software up to date. It’s best to let these processes do their thing to keep the system current and secure. The Software application will typically notify when software needs to be updated and provide an interface for doing the update.

Using the Command Line

I’m a dinosaur. In spite of what I’ve written here, I pretty much always use the command line to update my systems. This way I can update computers remotely and not bother sitting at the terminal for each to keep them updated - some don’t even have a terminal to sit at! It can also be scripted and automated from the command line whereas using the GUI tools would be “inconvenient” for that purpose.

To give a high level flavour of what this looks like under Debian based systems it’s something like:

1apt update

2apt upgrade

3apt autoremove -y // if appropriate

Each step needs to be inspected for errors and warnings and reacted to as required. Depending on the scale of the update (kernel update) a reboot may be merited.

Arch, Fedora, and other distribution types have similar methods.

Flatpaks?

1flatpak update

Repository Software Is Too “Old” Or Software Is Not Available?

Sometimes, when using a LTS (Long Term Support) Linux distribution, the repository software versions may be older than you want.

A good example of this is when an LTS distribution is released just before a new major release of an application that you use regularly. An application like the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) may have version 2.x in the repository while a huge update with many desirable features is available in the 3.x release.

There are a few approaches that can be taken: find a Flatpak version, find an AppImage version, or compile from sources.

Flatpak and AppImage are a valid path forward in the majority of cases. This applies mostly to graphical, desktop type software.

Compiling from sources are a headache beyond getting the software to compile (future maintenance). That will be expanded upon below.

Technical Information About Installing Software

Distribution Repository Packages

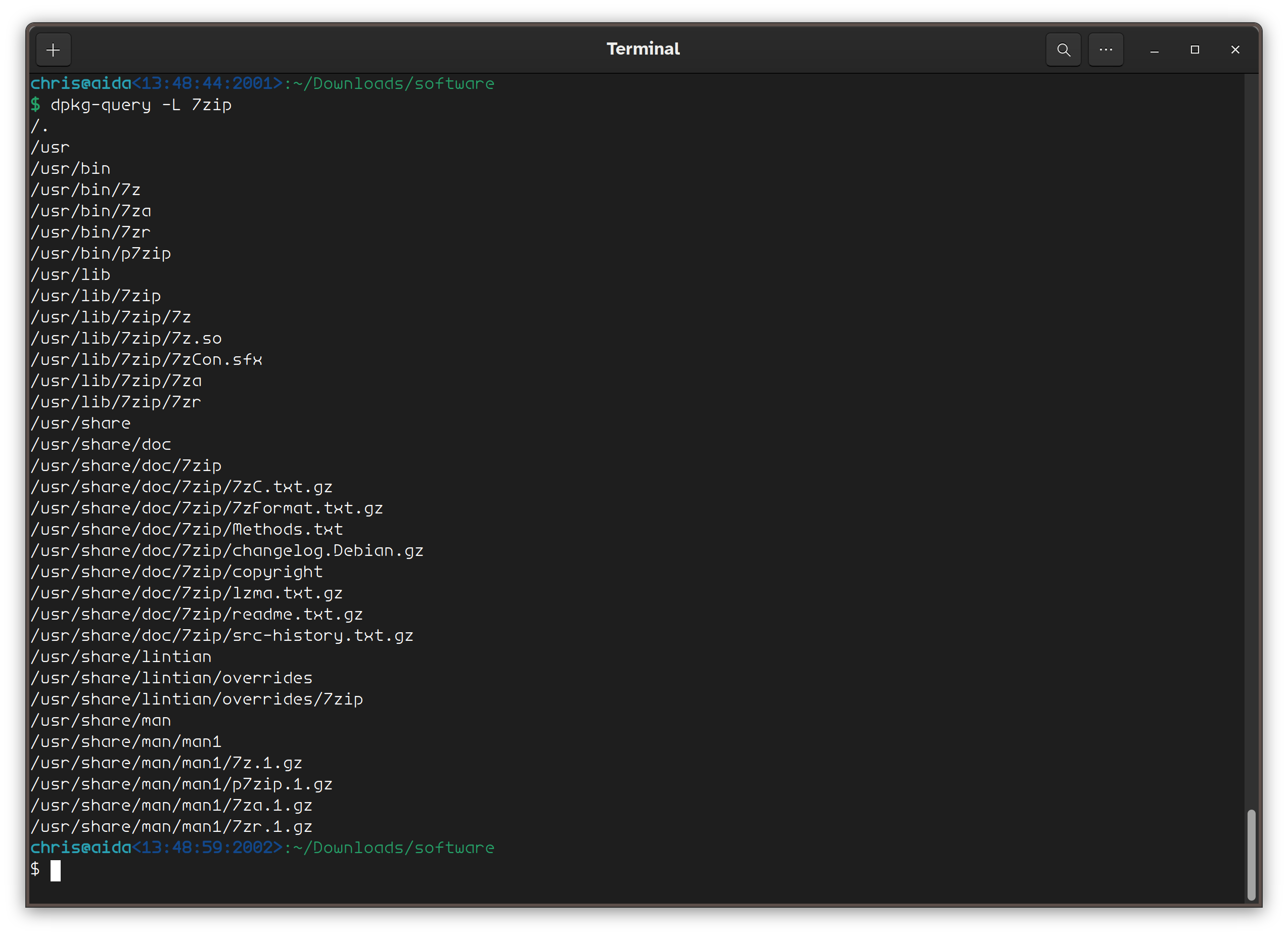

When a package is installed on your system there are various files installed in different locations. As an example, let’s take a look at where a small command line program like 7zip installs files on the system.

From this listing using the dpkg-query command, we infer that the binaries for the program are installed in the standard binary directory /usr/bin and function library files are installed in /usr/lib. Other distributions have similar tools for this kind of package investigation.

The /usr/share directory holds system accessible extra content for a program package. The docs and man (i.e. manual pages) directories are obvious. lintian is related to the Debian apt package checker.

This is a simple program. Larger programs and programs with elevated security requirements will copy files elsewhere.

Because this program was installed using the distribution’s package manager, a command can be run to delete the package and it’s related files from these locations. In some cases where configuration is written to the /etc directory, the package manager may leave the /etc files behind and rename them.

When you install a modern, graphical application like LibreOffice and run it for the first time, the program will typically create files in two locations.

The .config directory in your user home directory is used for application configurations. In the case of LibreOffice the directory will be /home/username/.config/libreoffice.

In the case of LibreOffice additional fonts will be installed in the /home/username/.local/share directory. This share directory is analogous to the /usr/share directory in the 7zip example above but since it is in the user home directory it can be written to by the user and root (system administrator) access is not required.

If LibreOffice is uninstalled, the user .config and .local files will be left behind. Reinstalling the software should pick up the same, existing configuration. These files and directories are small and don’t use up a lot of diskspace. But if you don’t use a specific application any more and really doubt you will ever install it again, it may be worth doing some clean up in these directories. Be careful!

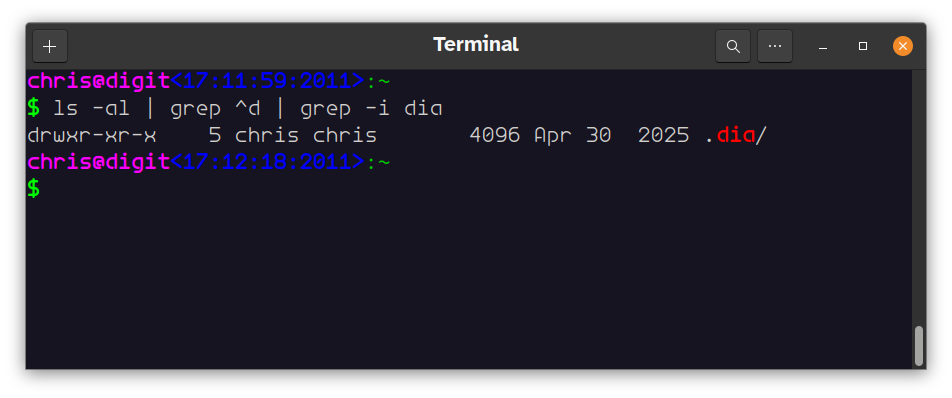

Other applications, particularly older ones that were around before the FreeDesktop standards became mainstream, will write their configuration files in the user home directory. An example in my home directory is the configuration directory for the Dia diagramming tool.

Does all the above seem really complicated and like a lot to manage? Use the software application for your distribution to install and delete software and forget about it.

Flatpaks

Flatpaks are great in that they are becoming a new standard of sorts for software delivery. There has been a lot of uptake from software projects to use Flathub (the main Flatpak repository) as one of their primary methods for software delivery.

This is a two fold win in that it makes the most current and up to date software available to all Linux users, including those on older LTS distributions, and it ensures that the software being delivered has the author’s intended base configurations and defaults in place.

In some cases distributions have taken the further step of completely integrating the flathub software delivery mechanism into their base install as an “out-of-the-box” feature.

For distributions that do not have Flathub integration installed by default, there is work to do to install Flathub. Instructions for this can be found on the flathub.org site for pretty much all Linux based operating systems.

It is important to pay attention to where a flatpak comes from and who created it. Even on an “official” site there may be multiple versions of a flatpak: the official version, a version created by an enthusiast with specific configuration choices, and versions that may have been created for other unknown reasons or to deliver malware. When possible always pick the flatpak created by the software’s actual author. Other versions can be good if you can discover the backstory from social media or forums.

Flatpaks create a sandboxed application on your computer? What does that mean? The app is running in it’s own self-contained environment and does not have direct access to the operating system it is running upon except through very specific, pre-configured interfaces.

Why do we need to know this? Sometimes you need or want to set some custom environment variables for the application to use or configure some custom gsettings if it is a GTK application. Because the application is sandboxed there is a layer of abstraction to work through to set these custom configurations.

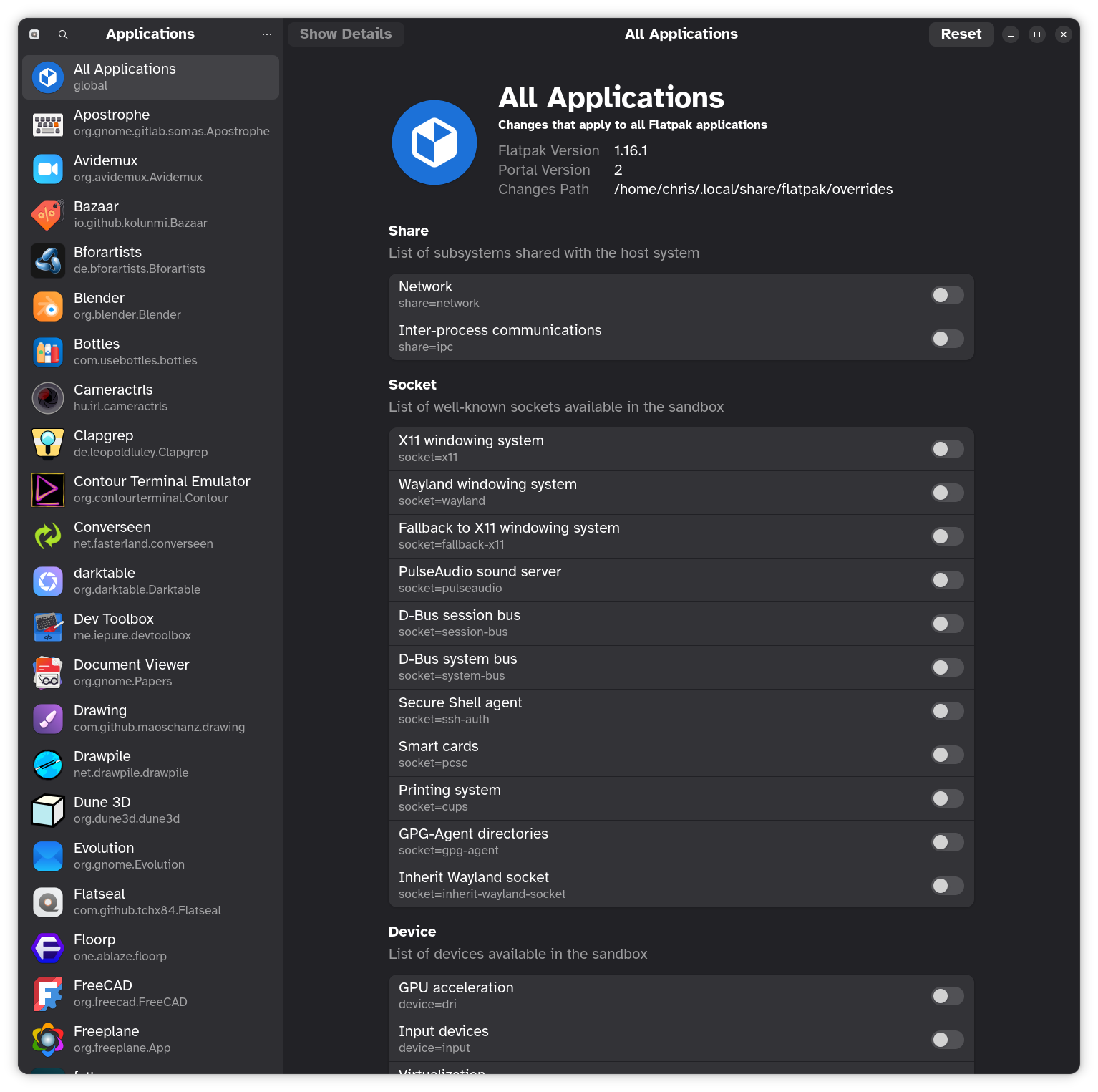

Flatseal is a great app for doing some of this configuration.

Sometimes you need to directly configure other settings as if the application was running on the bare operating system. There is a method to get shell access to a flatpak and I’ve written about it here: How to access the command line inside a flatpak

AppImages

AppImages are another method to distribute software. Again, this is an entire application bundle sandbox with it’s own operating system libraries and whatnot.

AppImages do not have a centralised distribution platform. They typically are downloaded from a project’s web site and it is up to the user to figure out what to do with them.

Also, like flatpaks, it’s important to know and trust the source of an AppImage.

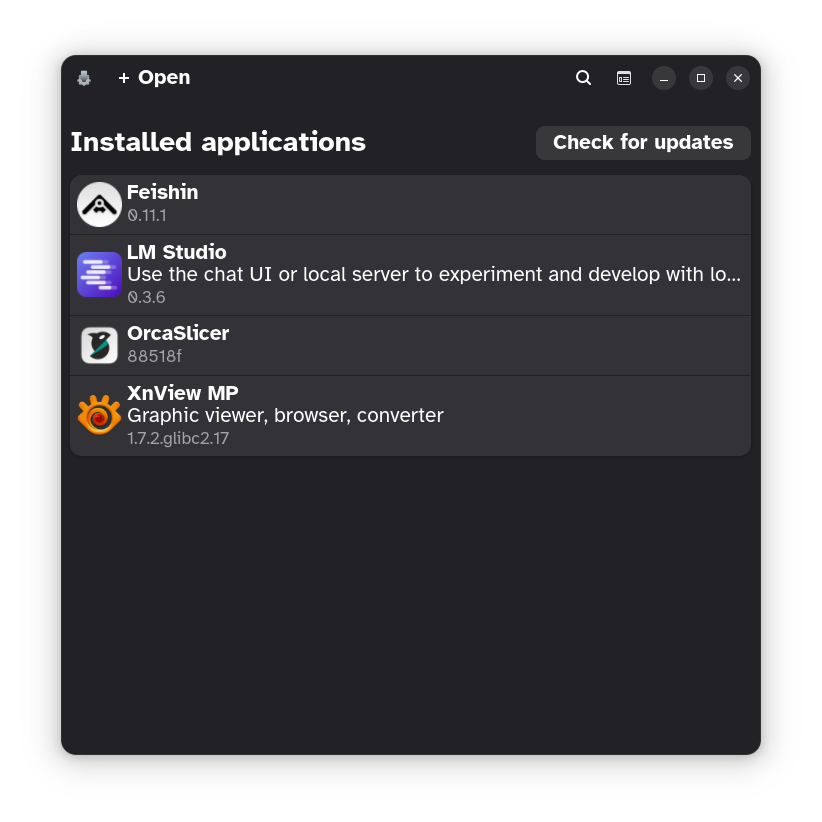

Gear Lever is a great application for managing these downloaded images. It will copy the AppImage to a pre-configured location and mark it as executable.

Snaps (Ubuntu)

Ubuntu has it’s own proprietary snap packaging system. I don’t use it and don’t know a lot about it. It seems like it is analogous to Flatpak but if you are really interested in it then I’d suggest doing further research.

Compiling from Source

Compiling from source is a not very straightforward. The high level, broad strokes are:

- Obtain the source code via downloaded tar ball, git clone, zip file, etc.

- Read the included README file included in the source code bundle if it exists.

- Verify the tooling requirements in the README exist on your computer and install them if required.

- Depending on the source code type, configure may be run to help determining requirements and configuring the build.

- Run make or equivalent depending on what language was used to write the source code.

- Run make install or equivalent depending on what language was used to write the source code.

- Run the app!

Sounds simple enough, right?

There’s lots of ways this can break your operating system. Depending on the package you are compiling the make install step may overwrite your distribution’s pre-packaged binaries or libraries that live in /var and /usr and cause version or architectural issues - or just outright break the system.

Also, now you are responsible for keeping that software up to date and applying security patches. Oh joy!

Back in the 1990’s we compiled most all of our software because that was the way things were done. Nowadays I avoid it as much as possible. I don’t miss it - at all!

If you do have to compile software, consider setting up a virtual machine or containers to experiment. If you blow up your virtual device it’s no big deal.

Docker & Podman Containers

I’m a big fan of using Docker/Podman. It’s a form of virtualisation to separate a program from the underlying host operating system.

What I like about it is that if gives the opportunity to try out software without the installation of the software’s associated dependencies and libraries and messing up the hosting computer’s operating system. You don’t have to worry about library “versionitis” or overwriting a distribution’s version of software. It allows using the latest, greatest versions if you are using an LTS distribution with lagging packages.

An example that I use regularly is installing Samba via Docker. It’s fully self contained and the links to resources are explicitly controlled. I also allows installing the latest version of Samba if the distribution repository is lagging.

I use it on servers as well. Typically, every user facing service is set up as a docker container for isolation and management.

Setting up containers is beyond the scope of this document.

Other Methods and Sources

Python software has a neat command line software manager called pip. It works similarly to operating system style tools with install, upgrade, uninstall, etc. style operations.

Arch Linux has the AUR (Arch Linux User Repository) which has a lot of additional software for Arch outside of the official repository. The tool yay can be used to directly interact with this repository.

Fedora/RHEL based distributions can make use of the *EPEL (Extra Packages for Enterprise Linux) repository. The standard commands can use this repository once it is configured in the operating system.

Final Words

I hope this gives some context around managing software under Linux.

In a nutshell:

- lean towards using your distribution’s repository software as much as possible and where it makes sense,

- leverage flatpaks and AppImages if you need more up to date versions of software or software that is not available in your distribution’s repository,

- avoid compiling software, and

- consider using containers if it makes sense in your use case.

Further Reading From This Site

Some other posts that may be of interest:

Linux:

Gnome Desktop:

Linux Packaging: